In the beginning there was the word.

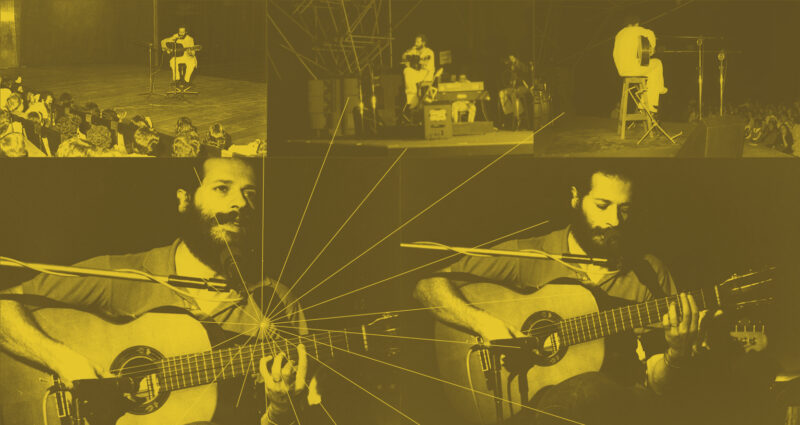

No. In those nights of 1978, on the dark stage of what was then Sesc Vila Nova, now Sesc Consolação, in the beginning there were only inarticulate sounds, as in the chaos of any origin, gradually forming rhythmic patterns, with percussion beats on animal skins and shouts merging into musical language, already as part of it. It was the beginning of João Bosco’s show.

The long initiator and initiatory ritual does not fail to narrate, initially without a single word, based solely on Afro-Brazilian drum beats1, the genesis of human language (which, according to the current state of contemporary science, would have originated in sub-Saharan Africa over 100,000 years ago), gradually forming through shouts, interjections, and then proto-sentences, the meaning of which we still don’t fully understand.

What is being told, however, is, at the same time and above all, the genesis of a biosociocultural process, which is the very formation of Brazil itself. The perspective here is that of a deeply Africanized Brazil, gestated in the batuque2 of enslaved black people, in the Afro-Tupi blood, in the barbarism and barbaric freedom of the colonial period. The six or seven minutes of batucada tell this whole story, this sort of forceps birth of a community that was “born in suffocation” – as we hear when the Portuguese language finally emerges, this last flower of Latium, or rather, this African sprout, flower from Luanda, with a Tupi substrate, as Caetano Galindo called it.

The Old Testament is thus translated into the reality of Brazilian formation, with the original birth taking place in the presence of a “cow, a donkey, and a madman” (vaca, um burro e um louco), in the middle of the “mud, instead of incense and myrrh” (barro, ao invés de incenso e mirra), and the “cord cut with a razor blade” (cordão cortado com gilete). In the Brazilian Nativity Scene, the manger is a hot plate, and when the boy is born (Brazil, the boy), someone grabs the heater, draws a knife, a samba leader starts a samba, and Oxum prophesies: this one seems promising. This is how this Relicário opens the curtains of Brazil’s past, present, and future. Querela instead of Aquarela3.

In this context, Relicário is not just a place – the theater, the show – where a series of relics, the songs, are kept and presented. The religious dimension of the word (relics used to be images of saints) is connected to this subverted genesis – no Wise Men: cow, donkey, and madman – which foreshadows a corrosive and tender feeling, thus taking on an ironic and affectionate tone, a tone that marks a good part of João Bosco and Aldir Blanc’s work (in this show directed by Paulo Emilio, a partner of both in some important songs).

In this extraordinary opening, almost eight minutes long, we are introduced to the cosmogony of the partnership that narrated the Brazilian experience during the years of dictatorship with a richness and harshness rarely comparable. It’s 1978, in the period of diastole, to use the cardiac metaphor of General Golbery’s decompression, the regime’s main ideologue. The Amnesty Law would be promulgated the following year. Nearly fifteen years of dictatorship had already passed, but only seven years since the phonographic debut of the Bosco/Blanc partnership, on the 78 rpm record of Pasquim’s pocket collection, with the song “Agnus sei” (which, just like in “Genesis,” also turned Christianity upside down). On the other side of the record, the already acclaimed Tom Jobim presented none other than “Águas de Março” and legitimized the Mineiro-Carioca (or more precisely, Ponte Nova-Tijuca) duo.

The duo’s first LP would be released the following year. João Bosco, with a portrait of the composer painted by Carlos Scliar, shows a work that was already powerful from the outset but still somewhat indecisive in the face of so many possibilities. The album is a brilliant debut and has almost all the elements that would solidify the duo’s identity: the social portrayal of the working class (“Fatalidade: balconista teve morte instantânea“, “Tristeza de uma embolada“), a combative action, like cultural fighting cocks, confronting the shallow consumer capitalism (“Tristeza de uma embolada“, “Nada a desculpar“), the head and pen of black men (“Quilombo”), the invoked samba (“Bala com bala“), the baroque heritage of Minas Gerais (“Angra”), the exceptional guitar work, both rhythmically and harmonically, dense yet captivating melodies, equally dense lyrics, but in service of rhythm and melody, simultaneously transcending music and remaining true to the overall song’s purpose.

All these traits, and a few more, would be perfectly defined from the next album onwards, Caça à Raposa, a collection of hits and masterpieces that enjoyed great success in terms of both audience and critical acclaim. Caça à Raposa includes everything from the brief cubist epic (to escape censorship?) of the eponymous song, made up of shattered verses under a moving melody, to the fast and masterful samba “Kid Cavaquinho” with its irresistible breque 4and refrain. Passing through some of those absolutely perfect sambas, like “De frente pro crime” and “O mestre-sala dos mares“, and also through an equally perfect samba, “Escadas da Penha“, but with a very daring formal structure, including a six-eight time signature inserted in the middle of the battle, and a rearrangement of the word order in the verses (as Chico Buarque did in “Construção“).

Next, Galos de Briga solidifies the work (even more hits, even more jewels), a strikingly successful entry into the national songbook. The album opens with “Miss Sueter“, a beautiful bolero, with one of Aldir’s lyrics that stand in a disconcerting place between irony and sincerity, parody and tenderness (personally, knowing the author, I am certain that the cultural and human attitude there is, deep down, profoundly loving). It also features two absolutely perfect sambas, “Ronco da cuíca” and “Incompatibilidade de gênios“, a contagious marcha-rancho “O rancho da goiabada“, which narrates the role reversal of carnival, when the boias-frias become “clowns, Martians, cannibals, crazy lilies” (palhaços, marcianos, canibais, lírios pirados) – as well as other gems like “O cavaleiro e os moinhos” and “Transversal do tempo.”

The next album, Tiro de Misericórdia, was released amidst a personal weariness of the partners, which João Bosco openly addressed in an interview with the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo, on the occasion of the debut of the show at Sesc in 1978: “The work we’ve done in nine years has defined a line of conduct, a critical view of reality that won’t be abandoned.” Indeed, the following album, Linha de Passe, would feature several songs by Aldir, including the exceptional eponymous samba, the sharp partido-alto “Boca de sapo“, and the opening anthem, “O bêbado e a equilibrista“. The widely publicized personal estrangement of the duo thus did not in any way compromise the quality of the songs, in the subsequent years when the work continued and/or a precious treasure trove was released to the public. On Tiro de Misericórdia, the title track stands out, a kind of Bildungsroman of the periphery of capitalism, a coming-of-age novel of a young black man from a Rio de Janeiro favela, complete with African diaspora religiosity, revolutionaries of all kinds – and a black body “savaged with over a hundred shots”. All of this is presented in a guitar rhythm with João Bosco’s unmistakable right hand style, both a terror and a glory for amateur – and professional – guitarists.

Relicário extracts its relics from this still brief (a single and four LPs), yet exceptional, set of songs. Many of the songs I’ve discussed here, representing various facets of the Bosco/Blanc duo, are present in the show. Paulo Emilio, the director, stated in an interview at the time that he structured the show around four axes: childhood, discovery of life, social chronicle, and “synthesis of everything.” Forty-five years later, I believe that this division loses some clarity, as we inevitably listen to the set with many other background information. What prevails, in my view, is a grand fresco of the Brazilian experience during that contradictory period, of aesthetic deepening and regression of the social utopias of the 1960s.

A fresco in which we can see both characters from the working class amidst urban violence (“De frente pro crime,” “Tiro de misericórdia“), the explicit state of exception of the dictatorship (“Caça à raposa“), and economic poverty, “where so many equals gather, telling lies to bear the burden.” But where we can also see the pains and delights of subjectivity, especially suburban (there’s no Ipanema in this universe): the forgotten unforgettable beginning, comets traversing the sky of the mouth, the artist’s soul and the tremors in the hands, the “gardenia perfume”, the whisky with guaraná. References and reverences to the way of life on the other side of the Rebouças tunnel, to which Bosco and Blanc connect, after the coastal and cosmopolitan Rio de Janeiro experience of bossa nova; the pop pessimism, Brazilian and global, of tropicalismo, and the gypsy counterculture, with touches of Beatles and o dedo de Deus in Milton Nascimento and Clube da Esquina’s repertoire.

During this golden period of popular song (as rich as that of the 1930s/40s), Bosco and Blanc both articulate the legacy of Estácio’s samba (and, before it, its African matrices) and its modernization by João Gilberto – but shift the narrative toward the lyric-social chronicle of the Rio de Janeiro suburb. João Bosco’s guitar comes from Dilermando, Garoto, Caymmi, João Gilberto, and Baden Powell – and goes beyond them, forging his own path. The sense of rhythm comes from the African world and the Latin American bolero. The soul is impregnated with the baroque of Minas Gerais and Luso-Arab resonances. Aldir is capable of reconciling the tradition of social chronicle – portrayal, humor, and lyricism – with a formal composition worthy of the most advanced experiences of high modernism. Vanguard and suburb. Formal excellence and expressive portrayal of the peripheral people’s way of being.

It is no coincidence that “Tiro de Misericórdia” is the song that concludes this profane Relicário which began with a farce and ends with an execution. In just nine years of partnership and seven years of public work, Bosco and Blanc had composed a grand fresco of Brazilian life under the generals’ boots. They sang the multiple forms of popular religiosity; the joy sprouting like a flower from the asphalt facing the crime; the characters of counter-political history, like the black navigator, mestre-sala of the seas, Admiral João Cândido; suburban love, conveyed in a mixture of lyricism and self-irony that is perhaps unique to this duo; and much more. All this in a formally inventive structure, high complexity almost miraculously reconciled with simplicity – which, in any case, remains perhaps the best definition of the great tradition of Brazilian popular song.

Notes:

1 Batucada used by the author means both drum beats or a style of samba with African roots.

2 Ibidem

3 The author plays with words based on the songs Querelas do Brasil, written by Maurício Tapajós and Aldir Blanc, and Aquarela do Brasil, written by Ary Barroso. Querela has the meaning of quarrel, i.e. lament or complaint; in the case of the song, a lament for the fact that the Brazilian economic elite suffocates the country’s popular culture, evidenced in the lyrics by lines such as “Brazil doesn’t know Brasil”.

4 Meaning both “break” and samba de breque, a subgenre of samba, which uses sudden stops, usually of a humorous character, in which the singer makes spoken comments.

Francisco Bosco is an essayist, doctor in Theory of Literature and popular music lyricist. He founded and coordinated Rádio Batuta, from Instituto Moreira Salles.

About Relicário: João Bosco (Ao vivo no Sesc 1978), you may also read:

Utilizamos cookies essenciais para personalizar e aprimorar sua experiência neste site. Ao continuar navegando você concorda com estas condições, detalhadas na nossa Política de Cookies de acordo com a nossa Política de Privacidade.